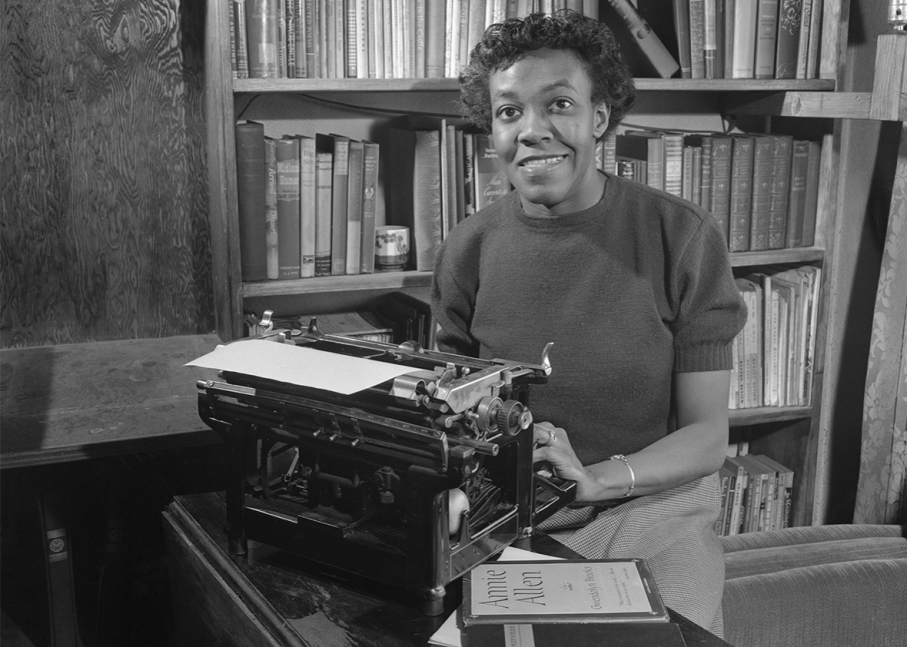

Gwendolyn Brooks on May 2, 1950.

Often, the best works of art about an historic event come from long before. Here are the four poems from the past—as I posted in Slate on November 17—in response to the 2016 Presidential election. For this Forum, an audio file for each poem.

First, Walt Whitman’s “Election Day, 1884” written about the nasty Cleveland–Blaine election of that year. Whitman says that the heart of the election is “not in the chosen” but with “the act itself the main, the quadrennial choosing.” He speaks of voting day not as sacred but as “powerful,” comparing it not to forest glades or solemn cathedrals but to the fluid, dynamic energy of Niagara Falls.

Nicaraguan poet Ernesto Cardenal’s “Somoza Unveils Somoza’s Statue of Somoza at the Somoza Stadium” imagines the voice of egomania in power. The poem’s concluding insight about hate, a terrific final chord in Donald Walsh’s translation, hisses even more effectively in the second person plural familiar of the Spanish: “la odiáis.”

Gwendolyn Brooks’ sonnet from her sequence The Womanhood uses that form to present the relation between art and battle, with their related priorities and demands: a practical, urgent struggle for a black woman poet of Brooks’ lifetime. “To arms, to armor,” she writes, with her fluent mastery of the sonnet form enacting a victory.

And as the final element in this little anthology, Czeslaw Milosz in his “Incantation” invokes the world as it should be and—the poem maintains—will be. It’s a kind of spell or prophecy by the Polish poet, who lived through both the Nazi occupation of his country and the succeeding Stalinist regime, to write this poem during his years in the United States.

—

Election Day, November, 1884

(Walt Whitman, 1884)

and show,

’Twould not be you, Niagara—nor you, ye limitless prairies—nor

your huge rifts of canyons, Colorado,

Nor you, Yosemite—nor Yellowstone, with all its spasmic geyserloops

ascending to the skies, appearing and disappearing,

Nor Oregon’s white cones—nor Huron’s belt of mighty lakes—nor

Mississippi’s stream:

This seething hemisphere’s humanity, as now, I’d name—the still small

voice vibrating—America’s choosing day,

(The heart of it not in the chosen—the act itself the main, the quadrennial

choosing,)

The stretch of North and South arous’d—sea-board and inland—Texas to

Maine—the Prairie States—Vermont, Virginia, California,

The final ballot-shower from East to West—the paradox and conflict,

The countless snow-flakes falling— (a swordless conflict,

Yet more than all Rome’s wars of old, or modern Napoleon’s): the

peaceful choice of all,

Or good or ill humanity—welcoming the darker odds, the dross:

—Foams and ferments the wine? it serves to purify—while the heart pants,

life glows:

These stormy gusts and winds waft precious ships,

Swell’d Washington’s, Jefferson’s, Lincoln’s sails.

LISTEN TO ROBERT PINSKY READ “Election Day, November, 1884”

* * *

Somoza Unveils Somoza’s Statue of Somoza at the Somoza Stadium

(Ernesto Cardenal, 1954, trans. Donald Walsh)

because I know better than you that I ordered it myself.

Nor that I have any illusions about passing with it into posterity

because I know the people will one day tear it down.

Nor that I wished to erect to myself in life

the monument you’ll not erect to me in death:

I put up this statue just because I know you’ll hate it.

Somoza desveliza la estatua de Somoza en el estadio Somoza

No es que yo crea que el pueblo me erigió esta estatua

porque yo sé mejor que vosotros que la ordené yo mismo.

Ni tampoco que pretenda pasar con ella a la posteridad

porque yo sé que el pueblo la derribará un día.

Ni que haya querido erigirme a mí mismo en vida

el momento que muerto no me erigiréis vosotros:

sino que erigí esta estatua porque sé que la odiáis.

LISTEN TO ROBERT PINSKY READ “Somoza Unveils Somoza’s Statue of Somoza at the Somoza Stadium”

* * *

“First fight. Then fiddle”

4 First fight. Then fiddle. Ply the slipping string

With feathery sorcery; muzzle the note

With hurting love; the music that they wrote

Bewitch, bewilder. Qualify to sing

Threadwise. Devise no salt, no hempen thing

For the dear instrument to bear. Devote

The bow to silks and honey. Be remote

A while from malice and from murdering.

But first to arms, to armor. Carry hate

In front of you and harmony behind.

Be deaf to music and to beauty blind.

Win war. Rise bloody, maybe not too late

For having first to civilize a space

Wherein to play your violin with grace.

LISTEN TO ROBERT PINSKY READ “’First fight. Then fiddle’”

* * *

Incantation

(Czeslaw Milosz, 1968, trans. the author and Robert Pinsky)

No bars, no barbed wire, no pulping of books,

No sentence of banishment can prevail against it.

It establishes the universal ideas in language,

And guides our hand so we write Truth and Justice

With capital letters, lie and oppression with small.

It puts what should be above things as they are,

It is an enemy of despair and a friend of hope.

It does not know Jew from Greek or slave from master,

Giving us the estate of the world to manage.

It saves austere and transparent phrases

From the filthy discord of tortured words.

It says that everything is new under the sun,

Opens the congealed fist of the past.

Beautiful and very young are Philo-Sophia

And poetry, her ally in the service of the good.

As late as yesterday Nature celebrated their birth,

The news was brought to the mountains by a unicorn and an echo,

Their friendship will be glorious, their time has no limit,

Their enemies have delivered themselves to destruction.